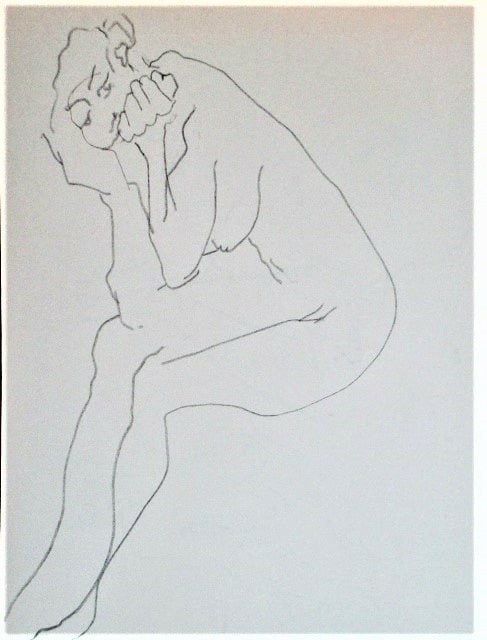

I turn to blind contour when I want to settle down a bit. I also find this method very helpful in bringing me back to a sensitivity of curve and direction of line.

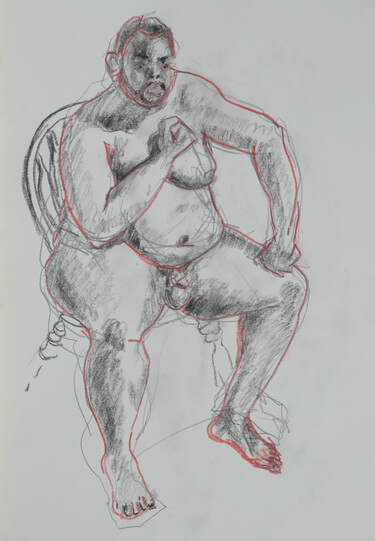

Clearly not even the third iteration is completely accurate. It would be easy to tighten it up, but that is not my preference.

Because I do not obliterate the earlier passes, I consider these drawings as examples of pentimento, the practice of leaving, albeit regretting, mistakes. Tongue in cheek, I sometimes refer to them as pentimentissimo, meaning the most regrettable.

Occasionally a blind contour drawing has just enough accuracy to be thoroughly humorous, and I leave it be.

*I remind the reader that I am committed to the use of the feminine form of the personal pronoun when referring to a person of undetermined gender, in case you are wondering if I am confused about my own.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed