Crystal Bridges Museum of Art

Crystal Bridges Museum of Art  The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. I grew up in its halls.

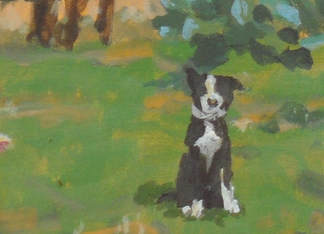

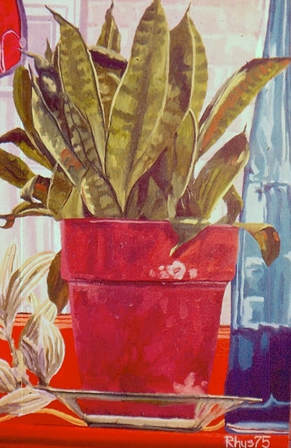

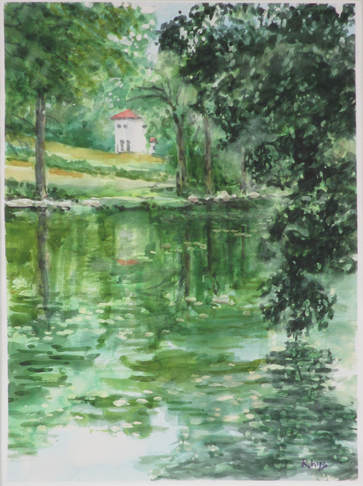

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. I grew up in its halls. The picturesque is the image that entertains us. It might be a nostalgic village scene, a depiction of family life, or the unusual. If a camera were available, a photograph could convey the same meaning.

The beautiful in art attracts us, and often thrills us. Even the ugly can be the basis of a beautiful painting, because the construction of the work itself inspires the aesthetic response. If it is the subject matter that is beautiful, as in a gorgeous sunset or flower, I would classify the piece as picturesque.

Pablo Picasso, Still Life with Pitcher, Candle and Enamel Pot, 1945

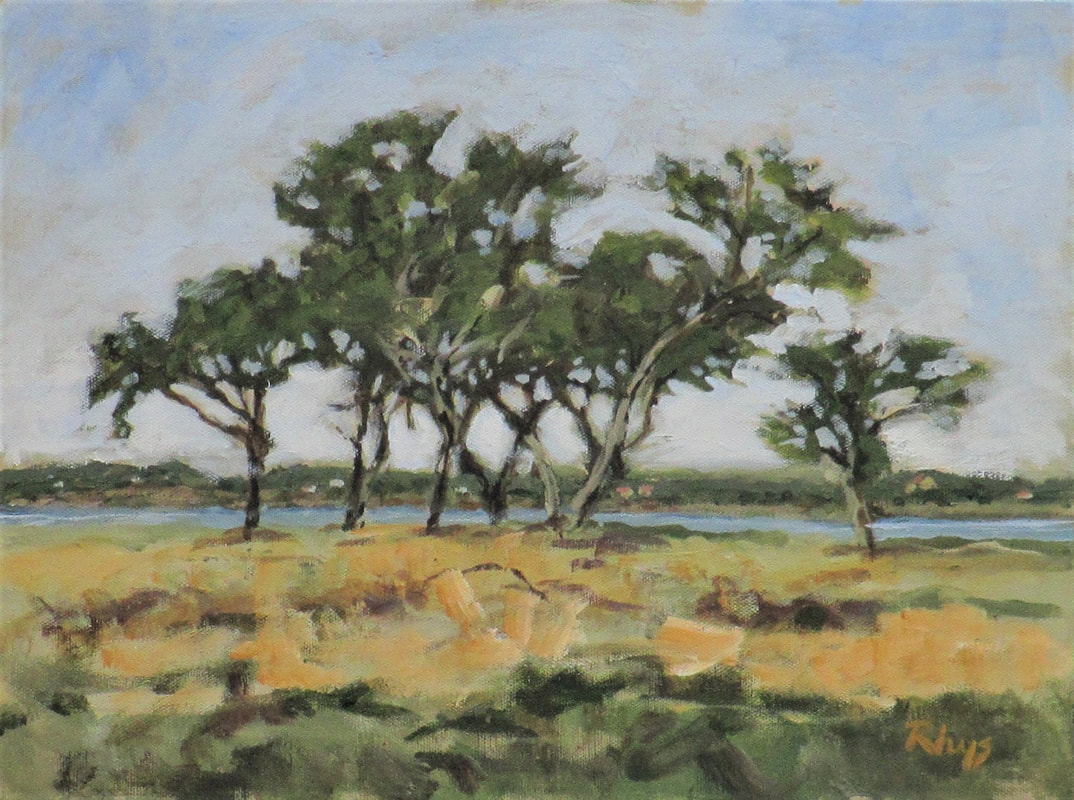

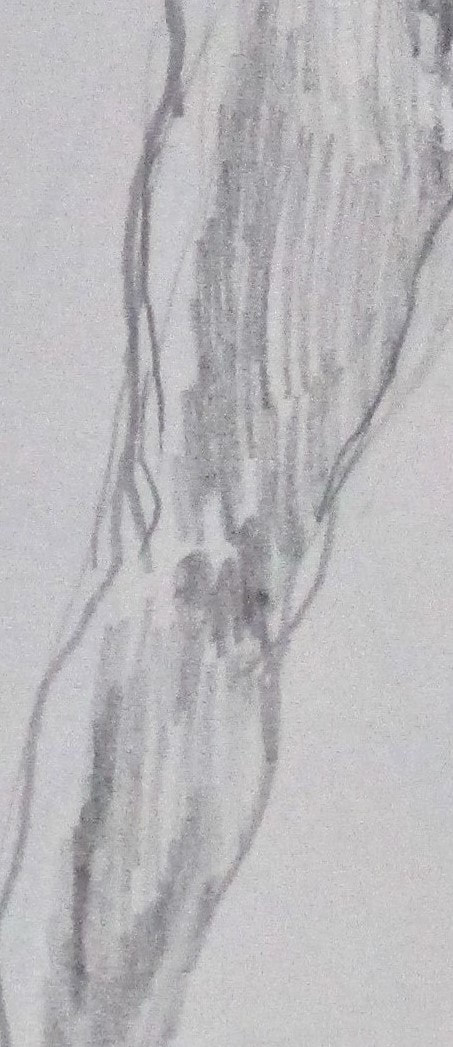

Pablo Picasso, Still Life with Pitcher, Candle and Enamel Pot, 1945 Impressionism was a sublime movement. Those guys woke us up to subtle color everywhere. And consider Cezanne’s delicate parallel strokes, Ellsworth Kelly’s great slabs of pure single colors, Egon Schiele’s ragged figures, Wayne Thiebaud’s desserts: doesn’t each of these lift us out of the mundane?

Shortly after my eavesdropping experience in the Crystal Bridges Museum I found myself classifying art into three new categories, according to our responses.

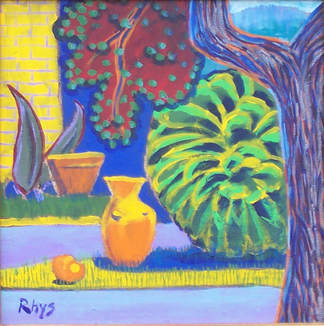

First is the pretty. Pretty pictures are highly valued thanks to a plethora of bright colors and graceful lines.

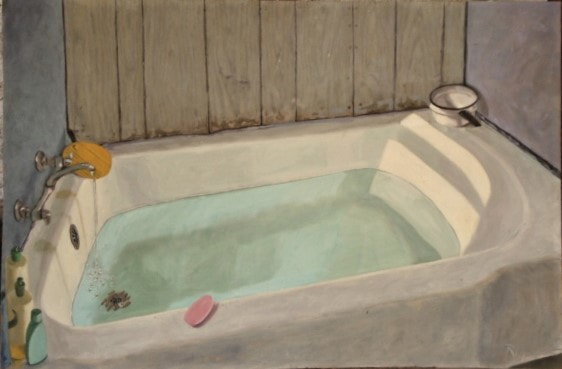

The second in this classification is the impressive. The viewer is impressed by detail, by photographic realism, or by an unexpected point of view. It might stimulate the artist to envy but not necessarily to emulate.

Inside the Guggenheim

Inside the Guggenheim

Does my classification match the professor’s? I don’t think it quite does, though their ranking in terms of quality might.

The Museum of Modern Art in New York. This photo brings back the feelings of excitement I once enjoyed there, though hordes of tourists with phone cameras have ruined it.

The Museum of Modern Art in New York. This photo brings back the feelings of excitement I once enjoyed there, though hordes of tourists with phone cameras have ruined it. I believe that a work of art can embody all of these qualities, and I am not ashamed of my pretty or my picturesque pieces. I am pleased when a painting turns out to be beautiful. I don’t know if my creations are ever impressive, but that is not for me to judge. I do strive to produce exciting and sublime works of art. I may not have succeeded in this aim, but I'm working on it. If my work fails to be pretty or impressive it is because I have my sights set on the uplifting.

It’s hard to imagine how one could find one’s own work sublime, and when I am excited by my own work it is usually because of an unexpected success.

The best we may expect of ourselves is to be as authentic and vulnerable as we can manage and leave the evaluation to others whose opinion we respect.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed