Walter's Window, ink on decaying paper, 24 x 18

Walter's Window, ink on decaying paper, 24 x 18 In February and March of 1964 I suffered a life-changing emotional upheaval, brought on by a severe case of culture shock in Sweden the previous summer, the assassination of President Kennedy the previous November, the worst math professor of all time, and, most significant, the powerful re-emergence of my drive to create art. I dropped out of Princeton University.

Through the luckiest chain of events, despite my poor father’s efforts to shoehorn me back into mathematics, I found myself—no, I wriggled myself into the design department of a local company, Rowe AC Manufacturing, the second largest maker of vending machines in the country, perhaps the world. And best of all, I fell under the mentorship of the best boss any fragile young person could hope for, Walter Koch.

I had had no formal training in art, despite requests for lessons I had made growing up, but Walter took me on—I have no idea why except for a remarkable charity. I just read in an old journal recently that he had told me he discerned my need for a father figure.

At some point during my first year at Rowe, Walter handed me a heavy zipper folder which contained two dozen pages of plastic color chips inserted into slots. Walter asked me to read the explanation pages of the chips and report to him, because he had not found time for it, and I eagerly got started. Soon he appointed me the eighteen-year-old color expert for the second largest vending machine company in the country. It was a very great honor and I studied and practiced even more.

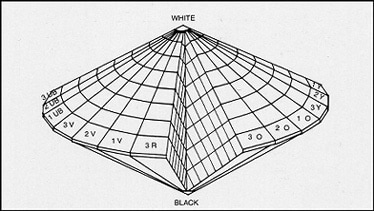

The book of color chips was a complete model of the color system of Wilhelm Ostwald. If you have seen a depiction of a color solid it was most likely that of Professor Albert H. Munsell. I had learned in a psychology class that color had three dimensions: hue, saturation and brightness. Those are Munsell’s dimensions. This, Ostwald’s, is not the same. Lucky for me.

Through the luckiest chain of events, despite my poor father’s efforts to shoehorn me back into mathematics, I found myself—no, I wriggled myself into the design department of a local company, Rowe AC Manufacturing, the second largest maker of vending machines in the country, perhaps the world. And best of all, I fell under the mentorship of the best boss any fragile young person could hope for, Walter Koch.

I had had no formal training in art, despite requests for lessons I had made growing up, but Walter took me on—I have no idea why except for a remarkable charity. I just read in an old journal recently that he had told me he discerned my need for a father figure.

At some point during my first year at Rowe, Walter handed me a heavy zipper folder which contained two dozen pages of plastic color chips inserted into slots. Walter asked me to read the explanation pages of the chips and report to him, because he had not found time for it, and I eagerly got started. Soon he appointed me the eighteen-year-old color expert for the second largest vending machine company in the country. It was a very great honor and I studied and practiced even more.

The book of color chips was a complete model of the color system of Wilhelm Ostwald. If you have seen a depiction of a color solid it was most likely that of Professor Albert H. Munsell. I had learned in a psychology class that color had three dimensions: hue, saturation and brightness. Those are Munsell’s dimensions. This, Ostwald’s, is not the same. Lucky for me.

Ostwald’s color solid is much neater than Munsell’s asymmetric color tree. Ostwald’s solid consists of two shallow cones, joined at their bases. Around the equator, or bases of this solid, are pure hues, twenty four of them. This equator is the color wheel with which we are all familiar. The axis of the solid is the gray scale.

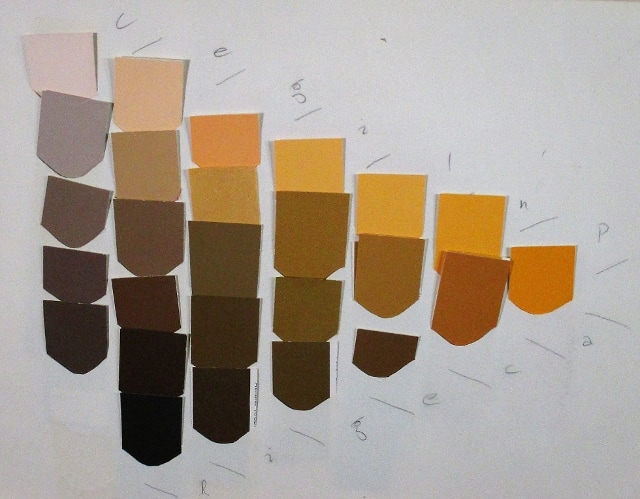

In the years after leaving Rowe I was unable to find another copy of Walter’s book and I had to build my own out of paint company color chips and the pages of a sketch pad. I placed the chips as best I could according to a book, not as good as Walter’s, that I found in 1976 on the fifth floor of the Los Angeles Public Library. A maniac has since burned that floor. I present a photo of one of my pages. As you can see, I was unable to find swatches for two of the colors. I meant to go back one day with my paints and create the missing colors on my pallete, but the firebug got there first.

In the years after leaving Rowe I was unable to find another copy of Walter’s book and I had to build my own out of paint company color chips and the pages of a sketch pad. I placed the chips as best I could according to a book, not as good as Walter’s, that I found in 1976 on the fifth floor of the Los Angeles Public Library. A maniac has since burned that floor. I present a photo of one of my pages. As you can see, I was unable to find swatches for two of the colors. I meant to go back one day with my paints and create the missing colors on my pallete, but the firebug got there first.

Imagine that I have cut a section out of the two-cone color solid. The vertex to the right, which would have come from the equator, is pure hue number 3. To the left of the triangle would be the axis of the solid, a vertical gray scale, but we don’t put it in because it is the same for each page.

Along the upper edge are colors acquired by mixing the pure hue with set percentages of white. These are the tints. (Please overlook the fact that these chips, coming from various sources, have not aged equivalently. One of them I cut from a paper bag!)

Along the lower edge are the shades, mixtures of the pure hue with black.

In the interior of the triangle are organized the tones: mixtures of hue, white and black. Along any descending (left to right) diagonal all the colors have the same percentage of black but decreasing percentages of white. Along the ascending diagonals, the percentage of white is kept constant. You should be able to see this for yourself.

Ostwald, you see, designates color according to hue, percentage of white, and percentage of black. Every color can be uniquely specified with just these three measures.

That’s enough technicalities for one day and I will end with just this: Using Walter’s book I trained myself to identify the exact hue of any color. I discovered that browns are red-orange in hue, skin is yellow-orange to orange regardless of race, and many colors we call olive green are just yellow. I wish I could assign you to look those up for yourself, but you have no book.

The best I can suggest is Ostwald: The Color Primer, edited by Faber Birren.

Along the upper edge are colors acquired by mixing the pure hue with set percentages of white. These are the tints. (Please overlook the fact that these chips, coming from various sources, have not aged equivalently. One of them I cut from a paper bag!)

Along the lower edge are the shades, mixtures of the pure hue with black.

In the interior of the triangle are organized the tones: mixtures of hue, white and black. Along any descending (left to right) diagonal all the colors have the same percentage of black but decreasing percentages of white. Along the ascending diagonals, the percentage of white is kept constant. You should be able to see this for yourself.

Ostwald, you see, designates color according to hue, percentage of white, and percentage of black. Every color can be uniquely specified with just these three measures.

That’s enough technicalities for one day and I will end with just this: Using Walter’s book I trained myself to identify the exact hue of any color. I discovered that browns are red-orange in hue, skin is yellow-orange to orange regardless of race, and many colors we call olive green are just yellow. I wish I could assign you to look those up for yourself, but you have no book.

The best I can suggest is Ostwald: The Color Primer, edited by Faber Birren.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed