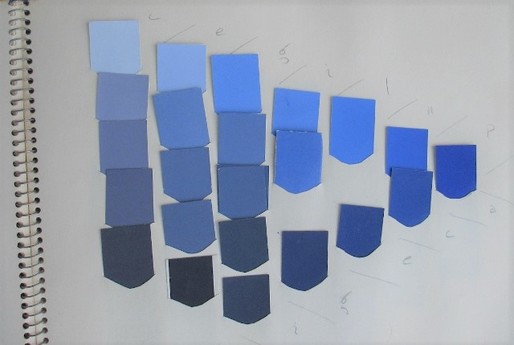

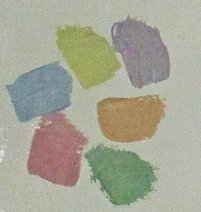

To begin, I have selected a blue page and pulled a series of colors from a diagonal that runs down and to the right. The colors to the upper left have an increasing ratio of white to hue.

Here is that whites group. Can you identify from where each chip came on the full-page chart? (You really should make your own series. The computer, in its certainty that it knows what we want better than we do, has hopelessly brightened my blue shade. This is the second row down.)

Finally, consider the colors taken from a vertical column. These colors all have the same saturation. In other words each color has the same ratio of hue to gray; the grays differ in their darkness.

Take a moment to enjoy these groups. They are not aggressively harmonious, but try this: mix a series for yourself and then include a color from elsewhere on the page and see if it “fits.” I remember going to a show of William Baziotes at the Guggenheim and being horrified to see him place saturated colors among the muted. I was more dogmatic then, but the combinations were unsettling.

Take a moment to enjoy these groups. They are not aggressively harmonious, but try this: mix a series for yourself and then include a color from elsewhere on the page and see if it “fits.” I remember going to a show of William Baziotes at the Guggenheim and being horrified to see him place saturated colors among the muted. I was more dogmatic then, but the combinations were unsettling.

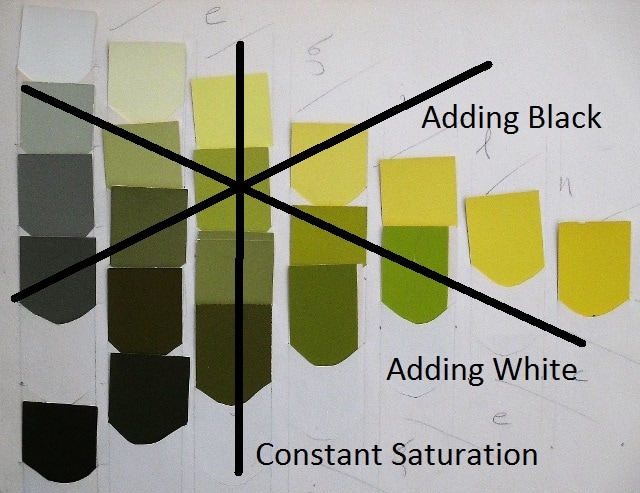

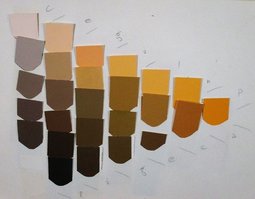

| When a saturation series, a whites series and a blacks series are chosen to converge at a single color we have what is called a star, all of whose colors harmonize as a cluster. When colors are jarring and I don’t want them to be, I consult the stars. We can build a painting’s color scheme (or troubleshoot a bad one) on a framework of stars from different hues, making sure that the centers of the stars match up like the combinations I demonstrated in the previous post. |

Below are three groups of harmonies made with chrome green. You can do this with any color, and it doesn’t have to be pure hue. In fact the pure hue doesn’t generate a star, as you can figure.

The vertical column of colors is accomplished by mixing a tint and a shade of equal saturation—to the best of my ability.

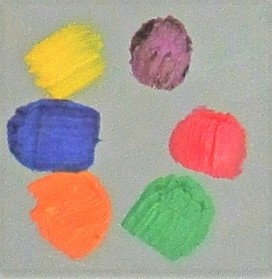

Now you try! Make a few still lifes using colors derived from hue, black and white, just to get the feel of it.

A final word in closing, to address the issue of value. You may have noticed that value is not one of the specified dimensions of this system, but you’ll also notice that value varies in every one of the harmony groups shown. Value may be the preeminent concern among many—or most—artists, but here are four ways to vary light and dark harmoniously, not randomly.

Now you try! Make a few still lifes using colors derived from hue, black and white, just to get the feel of it.

A final word in closing, to address the issue of value. You may have noticed that value is not one of the specified dimensions of this system, but you’ll also notice that value varies in every one of the harmony groups shown. Value may be the preeminent concern among many—or most—artists, but here are four ways to vary light and dark harmoniously, not randomly.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed