At the beginning of my color studies it amazed me to think that any color I could see had a well-defined place in Ostwald’s color solid. Could it be true that every color had no more than three coordinates? No color could slip out of the double cone and defy the system? No two different colors could have the same address?

Eventually I had to accept this non-intuitive truth: a color’s triplet of coordinates would nail it down. (I know now that there are several such systems, but I still prefer Ostwald’s.) What that signified to me, then, was almost miraculous: Each color has just three ingredients. According to Ostwald these were hue, white and black.

(Note: Color—anything that comes in a giant box of crayons, and more: white, gray, brown, bright blue, black. If you can see it, it is a color.

Hue—a color on the standard color wheel, or on Playskool blocks (do they still make those?). If a crayon says red, or yellow, that’s a hue.)

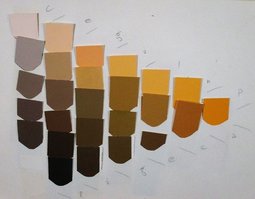

Since I had trained myself to distinguish the hue of any color, I decided I would begin the pursuit of a color mix with its hue, acquired by combining the paint-tube hues nearest the desired hue on the color wheel. For example if I wanted to match a brown whose hue I had discerned was red-orange, I mixed red and orange to attain the hue I saw in the brown.

Eventually I had to accept this non-intuitive truth: a color’s triplet of coordinates would nail it down. (I know now that there are several such systems, but I still prefer Ostwald’s.) What that signified to me, then, was almost miraculous: Each color has just three ingredients. According to Ostwald these were hue, white and black.

(Note: Color—anything that comes in a giant box of crayons, and more: white, gray, brown, bright blue, black. If you can see it, it is a color.

Hue—a color on the standard color wheel, or on Playskool blocks (do they still make those?). If a crayon says red, or yellow, that’s a hue.)

Since I had trained myself to distinguish the hue of any color, I decided I would begin the pursuit of a color mix with its hue, acquired by combining the paint-tube hues nearest the desired hue on the color wheel. For example if I wanted to match a brown whose hue I had discerned was red-orange, I mixed red and orange to attain the hue I saw in the brown.

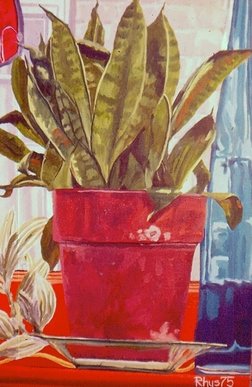

Measured use of black for a color match doesn’t deaden it any more than any other method of mixing a color; mixing with hue, black and white and holding up the palette knife to check taught me to keep shadows saturated, and to respect any hue shift.

Today I almost never mix colors using only hue, black and white, but thanks to many years of careful practice I am quite familiar with the color solid and can bounce around in it and still keep my bearings, confidently mixing any color I want to. If I get lost I can always go back to Ostwald. I may change my mind about what color I want, but can find whichever one I choose.

Next installment: Color Harmonies

Next installment: Color Harmonies

RSS Feed

RSS Feed