| Art school juries follow an almost indistinguishable practice, but with this one most important distinction: the art school jury is too often seeking to fault the student, who is expected to accept the question as a correctly negative judgment or to come up with a good story. This is called defending the piece. Need I say more? I advocate asking the question as a means of greater understanding. |

Poor Vincent! Today he is loved and admired by unthinking romantics. It is popular to believe that he painted the way that he did because he was such a beautiful character and that he could not really help himself. Those sinuous parallel brush strokes appear to have been made by a man who could not figure out what else to do, but at least he had gorgeous colors and curvilinear shapes. It doesn't occur to us to ask on any meaningful level, “What, Vincent, were you trying to do? Why did you paint that way?”

Do you suppose viewer comments bothered Van Gogh, especially from those who had no idea what he was really doing?

Vincent's intention, then, was to sacrifice a solid color or a smoothly gradated color for a more brilliant effect by alternating two similar colors.

By assuming that Vincent did not know any better, we have failed to learn of a major component of his mission.

When we walk into a museum and are faced with a large canvas painted with a single bright color we may react to the work of Ellsworth Kelly by assuming that he was just another minimalist, or that he was reacting against representational art or traditional art in some petulant way. But Ellsworth Kelly was one of a group of soldiers who, in World War II, created highly representational mock-ups of tanks, airplanes, and other military equipment in order to fool German aerial reconnaissance. His drawings of flowers are gorgeous, he was certainly capable of making thoroughly convincing representational art.

We may not be able to completely understand the relationship between his military career and his artistic career, but knowing just that simple fact about Kelly adds another dimension to the question of his later choice to reject illusionalism. He was far from inept at it. I do not want to oversimplify and suggest that Kelly was merely reacting against the war. He was operating on a much higher level of competence and sophistication in his artistic decisions than simple knee-jerk reaction.

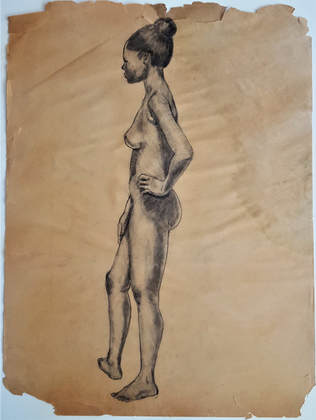

Regarding my own work I hope to hear not the vaguely judgmental comment, “That shouldn't work but strangely it does,” but instead the question, “Why did you do that?” to which I would hope to respond with an enlightened response. I, like most other artists, am not to be defined by my incompetencies.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed